The Invention of the Phonograph/Gramophone Morgan O’Beirne and Melanie Baker

The invention of the phonograph was groundbreaking. Music was now able to be heard one’s living room and nobody had to leave their home to hear their favorite symphony. Along with the invention of the phonograph came the idea of “good music” and what people thought that was. Europeans often viewed Americans as having poor taste, and in the excerpt from Katz’s Making America More Musical, it’s asserted that “Perception also held that only Europe produced what was known as ‘good music.’ (Its variants were similarly superlative: ‘the better class of music,’ ‘first-class music,’ ‘great music,’ and ‘the best music.’) While typically denoting the Western European classical tradition, the term good music harbored complex connotations.” (58) This way of thinking also contributed to the idea that jazz was thought of to be uncultured and vulgar; phonographs were now able to bring jazz into the home and the older generation was expectedly against this aspect of the new technology. They didn’t want their children to be corrupted by the “…sin in syncopation…” (58). Jazz, of course, is a genre of music African Americans created, so there was also the issue of racism connected to the contempt for jazz. Racial discrimination in conjunction with jazz caused concern with the advent of the phonograph because white people (again, especially those that were older) didn’t want that genre of music to be allowed in the home.

Another hotbed topic that arose from the invention of the phonograph was the concept of “feminizing” music. In the early to mid-twentieth century, it was seen as “womanly”—weak and un-masculine—to attend an opera or concert if you were a man. Although the purchasers of phonographs were largely women (and the advertisements catered to their domestic role), there was a push to market the invention in a way that also appealed to men of the time. Again, Kat’s Making America More Musical points this out in an analysis of behavior regarding the phonograph:

“But the phonograph had a significant impact on the male of the species as well. It offered something new to the average American man: a way to enjoy music without risk of being unmanly or, in the parlance of the day, “sissy” or “soft.” The phonograph also mitigated the supposed “feminizing” influence of music (particularly classical music), because as a machine it opened opportunities for tinkering and shop talk, traditional men’s activities. As one writer explained in 1931, ‘That men are notoriously fascinated by small mechanical details is a securely established fact. Well, then, is it any wonder that… men suddenly became profoundly interested in the phonograph?’… The fact that phonograph allowed men to listen to ‘good music’ at home was significant. Men could therefore experience the classics without the self-consciousness they might feel in public forums such as concert halls and opera houses” (66-67).

This excerpt highlights how much the female domestic sphere of the time had an impact on the way the phonograph was publicized and how feminized classical music had become.

Similarly, with the emergence of the phonograph came the “crooning” style of music. A normal volume of singing was much too loud to be effective through the phonograph, so the crooning style became popular. Music, Sound, and Technology in America as edited by Taylor, Katz, and Grajeda describes the reception of crooning in its early stages:

“Crooning didn’t grow only out of a technical problem, but also out of changing conceptions of American masculinity. The older, virile notions of masculinity seemed anachronistic to some in the early twentieth century. And the explosion of white-collar jobs in this era made it more difficult for men to conform to older notions of masculinity. Crooning was attacked for being effeminate and unmanly, and its fans were overwhelmingly thought to be women” (250).

The feminization of certain aspects of music can be traced back to the invention of the phonograph as one pinpoint for misogyny in the music world. For example, today, there’s still the underlying problem of instruments being gendered. Crooning suffered from the same toxic perception and the men who sang in that style were seen as softer than a “real man.” These societal concepts are important to remember when considering the history of the phonograph and the stereotypes that came along with it.

The following are articles of advertisements, concerts, and historical information about the gramophone from Evansville newspapers from the 1890s:

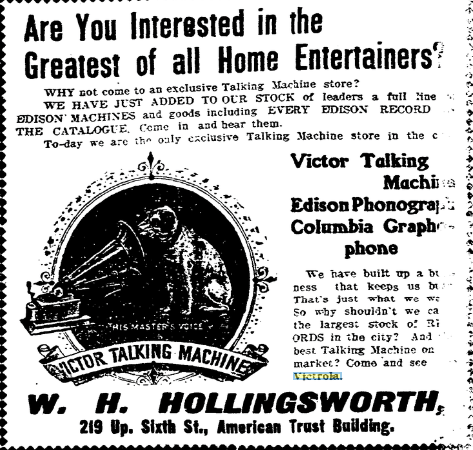

Evansville had no shortage of music in the private sphere during the late nineteenth century. With the capacities to record and publish music within the growing township, local composers took advantage of the opportunities that laid in Evansville. During this time, the city had sheet music stores, a “Talking Machine” store (see below), professional and amateur ensembles, and various venues downtown for public and private performances. Milton Tinker, a huge supporter of the arts, was the educational dean for the school corporation of the town during this period. Tinker made it a requirement for all children to be able to read, write, sing and play music, which cultivated a generation of the musically-literate. Evansville was a small town yet, but flourished in its capacities for possibilities in the arts.

The phonograph, Victrola, and graphophone were all manifestations of the growing music technologies that made recordings a possibility. The phonograph was an early sketch of the modern record player, which was later innovated as the improved graphophone. The Victrola was another patent of sound technology that was used for the first jazz and blues recordings. The Talking Machine Store was located in downtown Evansville, and carried a catalogue of Edison’s Machines to be used for recording purposes. This, in combination with the George W. Warren Publishing Company, paved the way for up-and-coming performers and composers to make their mark in history. Composers could publish their works, and amateur artists were able to create recordings of the newly published compositions for commissioning purposes.

Sources:

“Introduction.” Music, Sound, and Technology in America a Documentary History of

Early Phonograph, Cinema and Radio, by Timothy D. Taylor et al., Duke University Press, 2012.

Katz, editor. Capturing Sound. University of California Press, 2004.

Children’s Music in Southern Indiana

Madeline Cox

One very interesting collection of music was the collection of children’s’ songs that originated in southern Indiana. Though they were passed down by word of mouth, a man by the name of George List took the time in 1989 to transcribe a collection of recordings from the 1930’s. He interviewed children and adults who knew these songs fondly and would describe the games involved from the early 1900’s.

“The two principle childhood activities are play and learning, and the two have much in common since it is through play as well as directed activities that children learn physical and social skills. Thus, many children’s songs are based on aspects of adult life”.

-George List

One song in particular was the “Three Dukes” song. The game was played by a group of girls standing in a row. There could be many dukes, though it later was known that in Indiana there was only one duke. There were many different ways of singing and playing the game, but it always ended with a boy choosing a girl. This was said to be non-traditional and very skeptical. The idea was usually that boy would ask the parents’ permission to court the lady, but in these versions, the boy directly asked the girl.

Another popular song that was adapted to various clapping games was “BINGO”, which originated in England during the late 1800’s. This song has developed into a clapping and spelling game, where one child sits in the middle of the circle and points to different children in the circle. The kids have to spell the entire word, and if they mess up, the child in the middle takes their place.

Sources:

List, George. Traditional Children’s Songs and Singing Games in Southern Indiana. Midwestern Folklore, 1989.

Reitz Home Museum

Devyn Haas

While standing in the Reitz home you saw how beautiful everything was from the crown molding to the tiles in the bathroom. There were unique items that stood out to everyone. In there room where everyone gathered there was a harp along with a beautiful piano. The piano was a upright piano that was just gorgeous that drew all the attention away from the room until you turned around and saw the fire place. Once you walked into another room, similar to a family room there was another upright piano, along with a smaller piano, next to the smaller piano was a couch that had a lute. As you can tell music was important to the family, as it was to many other families. I think the most unique thing about the house is that there were musical items everywhere besides the instruments. The mother had a stained glass of an angel playing an instrument, along with a statue of a pied piper. In the father’s study there was a radio that apparently the father loved to listen to his music while he worked.